September 2022 | Digital Rights Regional Briefs

Danae Tapia, Global Community Manager & Resident Hechicera

Here’s a new release of our regional briefs!

This is the place to find updated and critical information about digital justice issues around the globe. Focusing in the Latin America, MENA, Africa and Asia regions, our reports cover Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders, Emerging Topics on Digital Justice, Community News, Regional News And Updates.

I personally recommend taking a look at the topic of loan apps reported by our Latin America and Africa researchers, an issue that can be tackled from so many perspectives beyond the merely technological.

And please contact us if you know about individuals or groups working on issues that should be reported in our briefs. Our intention is to adopt innovative perspectives away from mainstream discourses, and consequently, promote a more heterogeneous digital rights space.

Danae

Global Community Manager

Asia Regional Brief

Africa Regional Brief

Latin America Regional Brief

MENA Regional Brief

Author: Mardiya Siba Yahaya

Mardiya Siba Yahaya is our Africa Community Lead. She is a feminist digital sociologist, researcher , learning designer and storyteller whose work examines the internet and its cultures from the margins of gender and location. She has a Global Challenges degree from the African Leadership University, was awarded the Mandela Rhodes Scholarship in 2021, and is currently awaiting her Masters Degree in Sociology from the University of the Witwatersrand.

Africa Regional Brief

Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders

Feminist Review call for papers on its upcoming issue on Feminist Futures (Issue 136, March 2024) Submission deadline: 15 November 2022

Thorn is hiring for a Research Operations Manager to support a variety of individual research projects while driving operational efficiency in team processes and systems.

Emerging Topics on Digital Justice in Africa

How Digital Lending Apps Use Moral Shaming and Violate its Clients’ Privacy

Digital lending emerged in many countries as a solution to inaccessible banking systems and loans. Entrepreneurs and technology startups found a financial gap where many people who needed access to loans quickly had to go through tedious documentation processes. Many of these people were unable to provide the collateral and other documents needed to secure a traditional bank loan, so the loan apps addressed this hurdle.

The Systems are Designed Against Borrowers

While the lending process is relatively fast, and almost instantaneous, the interest rates are very high. The ripple effects of high and unregulated interest rates include borrowers not able to meet their repayment deadlines, because they are paying significantly more than they borrowed.

At the same time, the loan apps also require access to very sensitive user information before users are able to access the application. They use an ‘all-or-nothing” policy where the user must provide access to all the requested information from their device. Some of their policies state that the lender may use any information provided at their discretion to retrieve funds.They also collect mobile money or mpesa data to assess the borrowers’ ability to pay back. However, their process of determining credit worthiness is very elusive.

Personnels hired to follow-up on loan repayments shared that their managers did not care about the process they used to retrieve payment as long as they received their money, and the hired personnels met their stipulated targets.

As such, when borrowers miss their payment deadline, the loan apps begin to weaponize lending shaming as a tactic to make their clients pay. The issue of lending shaming is predominant in Kenya , Nigeria and most recently Ghana. The debtors send messages to the borrower's contacts, threaten their close friends and family, shame them in their workplace and send their employers messages that the said borrower is “a loan criminal”. There have also been cases where the debtors send out social media posts with images of the borrower who has defaulted on the loan.

The shaming, harassment and privacy violations of the loan apps are not isolated from the designs of existing financial institutions. For instance, in Ghana, until regulatory frameworks were implemented, there was a surge in microfinances who mostly targeted market women. Their financing model was similar to that of the loan apps, where loans were fast, and interest rates were extremely high. Market women received money as long as they had shops or stalls the microfinancing company could verify. However, just like the loan apps only this time in-person, they also used shaming and harassment to retrieve funds.

Moral Shaming and Privacy Violations

Private entities having access to sensitive data allowed them to surveil and morally shame their clients for not paying loans that have been inherent predatory designs.

In Ghana, Nigeria and Kenya, loan apps’ ability to collect and mine data while evading the right to privacy is because these jurisdictions rarely have the adequate privacy and data protection laws in-place. The loan startups have also been found to sell the data they collect to marketers and “share defaulters' details with credit reference companies, harming their future credit rating” further invading people's personal life and liberties.

There are various aspects to the potential harms and risks of technology that most policymakers and regulators do not anticipate or pay attention to. For example, if loan startups have access to a person’s data, including their personal contact, what are the potential uses of this information against gendered, sexual and ethnic minorities? Most of the violations happen within states that have historically and continue to target people based on their gender, sexuality, religion and ethnicity. While Nigerian and Kenyan lawmakers have begun to design policies to regulate what type of data the loan startups can collect, and the financial regulations they must follow, their regulations still do not protect marginalized communities.

In addition, if loan startups are able to engage in extensive forms of privacy violation, what other data is available to state and other private entities that can be used to target at-risk communities?

The Intersections of Surveillance, Privacy and the Deployment Digital IDs in Africa

We spoke with Amber Sinha who traces the origins of the deployment of ID for Development initiatives in the Global South. Amber also speaks on how researchers in various countries partner to evaluate the issues relating to oversimplified arguments of digital IDs put forth by state institutions. He helps us understand how the development of some of these systems amplifies and facilitates exclusion, surveillance, targeting of minority groups and predatory financial models such as lending apps’ privacy violations. Amber finally provides us with a perspective on how we can design privacy-focused and inclusive ID systems that do not further exacerbate socio-political and economic harm.

Q; Take us through your journey to working on digital IDs. How and why you began your work and digital IDs. What was the interesting thing you observed or identified that influenced you in getting into that space?

Amber: Being in India back in 2009, the government started a national identification project, which was intended as the largest identification project in the world. So that led to a lot of discussion, and at the time we did not use the term digital ID to describe it, we called it the national identification project. The project also made us consider a lot of privacy and surveillance issues. So this was regarding discourse around digital privacy, and it went hand in hand with the evolution of the Aadhaar project.

When the Aadhaar project was announced and created a lot of discussion, I started working in public policy a few years later. During that time, there was a lot of litigation against Aadhaar going on in the Supreme Court of India, which I followed very closely. And then I became part of meetings and the campaigns to rethink the Aadhaar project. I also started writing extensively and did a lot of research looking at the Adhaar big example of digital IDs and movements across the world. And at that point, I tried to sort of familiarize myself first and begin with answering , “what are the defining characteristics of a digital ID project and then try to locate it within the larger global discourse?”

Q: I see that Center for Internet Society (CIS) - where you worked - also did like extensive work on digital IDs, in Africa. What informed the decision to expand the case studies within different African countries like Nigeria with the National Identification Number (NIN), Kenya with Huduma Namba, and Ghana with the Ghana Card? These are quite interesting, given that most of the CIS team based in India.

Image’s source: Digital Identities: Design and Uses.

A: In 2019, we started a project moving on digital ID which did not only focus on defects but also one that looked at the design and development of different aspects of digital IDs.

So in the first year, the project worked on something called an evaluation chamber, which was a team that we created with partners across the world, i.e. civil society actors who could potentially hold their states accountable on the evolving or emerging ID programs. We launched it at Rightscon and the project garnered interest among different people.

Using our evaluation framework, we tried to test if we could work with partners in other parts of the world. Some of our partners in Latin America were interested in using it, other partners such as ITS Geo also decided to use it to assess ID programs in the context of COVID related technologies and contact tracing inside Latin American countries.

In addition to the evaluation chamber, we also published a series of seven case studies, four of which looked at use cases and three of which were looked at in countries we have already covered like India and Estonia. We also tried to extend the research into Peru, but this never materialized unfortunately.

It was around this time we began conversations with Research ICT Africa and we then jointly tried to fundraise to support the project in the region. In addition to our interest to extend our evaluation framework in other parts of the world, there was a huge push for digital IDs in Africa, we were particularly interested in working with researchers on the ground. With Research ICT Africa, we designed the project where CIS largely played a supporting and facilitator role as the creators of the evaluation framework. The case studies from Nigeria, Kenya and Zimbabwe were put together by researchers or civil society organizations that we identified in specific countries. We collaborated with researchers from 10 African countries with the idea that we consolidate the evaluation chamber based on how useful it would be in these contexts, and allow the researchers to apply the framework in their countries.

What are some of the emerging issues and trends that we should be concerned about regarding the deployment of digital IDs in the global south?

A: There are certain kinds of issues on Digital IDs highlighted ranging from privacy and surveillance, to exclusion and discrimination related issues. However, I think what we need to do is to take a step back and question the suitability of digital IDs, or at least the creation of digital IDs, and how it is being deployed in different parts of the world, particularly the Global South.

What is happening in many places is that the IDs are still being presented as a one-size-fits all solution that can address various problems. People try to retrofit all the problems to claim that IDs are the solution.

For instance, the problems of exclusion or the problems of leakages and corruption are not really ID related problems, but problems that exist at different points within the supply chain of subsidies of the dispersal of entitlements. But this being positioned largely as an ID problem, or it is being positioned as a problem having too many duplications of those in that network. The big challenge here is that with digital ID is that there isn't a proper articulation of the problem statement, and what digital ID is doing is often not the most suitable solution.

Also, without a proper analysis of what the suitable solution might be, there are large amounts of investment being made in creating these vast digital infrastructure systems. Meanwhile there are various things that need to come together for a digital ID system to work properly and I think the feasibility studies that are happening don't often take these issues into proper account. So it is a waste of resources because these are extensive and large scale projects being deployed.

The Privacy Problem. The other issue that I see is that there are particular versions of digital ID that the vendors have decided to put forth. Often what you see is the ID systems are centralized, they're biometric based, their designs are not privacy preserving and is driven by great hunger for more and more data by both the state as well as the private parties involved. Yet, that is not the only way in which ID systems can exist.

I can see ways in which digital identification solutions would actually be more privacy preserving than analog systems.

For instance, if you go into a pub, and in the country, there is an age limit on who can be served alcohol, often you are going to be asked for identification. In the way things currently exist, like an analog system, what you need to do is provide your passcode or some other form of identification, and apart from your age or date of birth, there is a lot of other information that can be accessed to your name or your address. Yet, I imagine that digital IDs with privacy preserving technology in place, the system would be designed in a way that the only information that they need to access is what they get. Which means that it is only your age they will be able to know to determine if you are of drinking age or not.

I also believe there are existing technologies that can render itself to use of this nature, which can be more privacy preserving. This is not centralized, not based on the idea of having more and more access to data at each point. But unfortunately, that is the version of ID systems that we see being deployed in different parts of the world.

Attempts to Address the Privacy Issue One of the things that we tried to do while I was at CIS, in the digital ID project was to come up with a decision guide for the design and development of technology and policy solutions, in an ID system. We tried to raise awareness on the alternative ways and choices that designers and stakeholders could make developing a system of that nature. But then there is also the issue of surveillance which is spoken about a lot.

Hence, the biggest issues are one, that ID systems are not created with the contextualized problems needed to solve in mind. And two, that we see only one version of centralized biometric based ID systems being pushed and there is a failure of the state which is not in a position to demand better of the vendors that it hires.

Q: We have seen increasing surveillance over the years, and currently loan apps collecting personal data from people who they lend money which they then use to target and harass them. What are some of the intersecting issues and how does the uncritical deployment of digital ID enhance all of that in the first place?

A: I think that is definitely going to be a huge issue. First you have to carefully study the various actors who are involved in ID systems and try to follow the money.

What becomes clearer in various contexts is that the ID systems are being created as a kind of platform surveillance system. So it provides a basic platform and it encourages different kinds of actors, both public and private, to leverage that platform to create services. Take the kind of service credit scoring, lending related issues that you mentioned.

These are also solutions that are often evolving in the absence of regulatory frameworks. So in many places, we don't have robust data protection regulation that can address the sharing and exchange of data from one particular use case of the ID system to the other. What we're seeing with the emergence of a lot of lending are also business models using IDs. Particularly, in relation to alternative data and small lending, the fear is that we might see some of the predatory practices that we've seen on payday links in places like the United States repeating itself here. However, here, this would happen in a completely unregulated economy.

The third issue that I see there is a set of discriminatory implications that might arise from that surveillance, because discrimination could be both direct and indirect. The more alternative data you have, the more scope you have to use proxy factors, which relate to protected characteristics such as race, gender, religion, and those can be used to profile you and then also disadvantage you in the financial ecosystem. Hence, there is one aspect of surveillance which is access to data that both the private sector and the state have.

Then there are also ways in which access to the data might manifest itself in disadvantaged outcomes for those communities. So these are some of the extreme and immediate real life dangers of the ways in which ID systems are being leveraged in many cases. There are also some jurisdictions that are going beyond credit scoring to some kind of social scoring algorithms, which is going to be even more problematic.

Surveillance definitely exists at, at multiple levels here. So far, we have dealt with a lot of first order harm arising from surveillance, but there are going to be so many secondary and tertiary order harms that can arise from the use of data like this.

Q: What are some of the invisible and underlying issues that we should really pay attention to? So, you know, it's easy for us to see certain things that are obvious regarding things like biometrics, digital IDs and whole ID for development programs. But if we are to address the root-cause, what should we pay attention to and how do we address some of these harms?

... more welfare governance ecosystems in the developing world in emerging economies are going to move to the digital sphere with the digital ID systems very much at the center. This gives the state even more power over oppressed communities.

A: The exclusion as an aspect of digital ID which has been spoken about a lot. But there is so much more that can go wrong with it. For example, during the pandemic we observed that there were several social welfare schemes emerging in different countries. Because of social distancing norms, again, digital ID was positioned as a solution. Also, this was something we saw happening mostly within migrant communities, to people who are undocumented and people who don't have the right domicile documents, which would give them access to entitlements.

There is a strange kind of socio-political problem it causes, where communities in various contexts, particularly around migration are affected. Some communities are for good-reason afraid of state surveillance, afraid of providing more information, and they are afraid of documentation.

Yet when you create systems where receiving basic entitlements such food subsidies are tied to an ID system of this nature, then obviously, it creates a situation where community members are often confused about the extent to which they want to be invisible, because on the one hand, they do want access to subsidies and entitlements, which are rightfully theirs. On the other hand, they are rightfully apprehensive of oppression from the state.

I think we are going to see more repetitive situations as things evolve, because more welfare governance ecosystems in the developing world in emerging economies are going to move to the digital sphere with the digital ID systems very much at the center. This gives the state even more power over oppressed communities. So I think that is going to be something that we have to work on which can be more inclusive.

Recommendations: Returning to the Fundamentals of ID Systems At the core any kind of ID system is a mechanism to establish trust. There are various ways in which we have established trust over time and that is essentially what the ID system does. It allows an individual to prove that they are who they claim to be. So what we have right now is a version of the ID system that is completely top down.

If you consider the technical documentation around ID systems, some of the documents that have come from previous privacy preserving suggestions come from the NIS Directive, which are the standard setting bodies in the European Union (EU). They speak about something called levels of assurance i.e. to access different kinds of service, you need to provide different levels of assurance. For example, to travel internationally, you need a passport, which is a particularly high level of assurance. If you are going to receive a delivery in your house, the courier company might ask you to show them a photo ID which they look at, but do not have to store the details. So, levels of assurance are designed from the perspective of Identity Fraud Management, assuming that people are going to game the system. Hence, directly answering the question of “how do we prevent identity fraud?”

The question that I ask is, if you are putting so much effort into systems to prevent identity fraud, then we need to ask, “how big of a problem is identity fraud that requires investment of millions of dollars to solve that problem?”.

The other part of the problem is the assumption that there are going to be socio-economic costs when somebody is able to successfully perpetrate identity fraud. Yet, there are bigger socio-economic costs when somebody is excluded [with the ID systems] because of glitches or exclusionary design of the system.

This means that to begin with, levels of assurance need to be reconsidered from the perspective of inclusivity. There are measures that you might put in place during the time of elections to ensure that there aren't many fake voters, but, in my view, the cost of a single person losing the franchise is quite high in any working democratic political system.

Alternatively we have to think of ways in which people in some situations can self assert their identity and that should be enough to provide them that entitlement. So, at the design level this is a problem where there is little consideration because a lot of focus is on how we make the central repository more secure, or how we create value in terms of access to data, all of which are important problems to solve. But I think at a fundamental level, we need to ask about the purpose of the ID system, and how and what is the primary problem in a given situation that it must prioritize?

Regional Update

In August 2022, the African Commission on Human Rights and Peoples Rights recalled its mandate to promote freedom of expression and access to information in Africa. The resolution recognises that rights protected offline through existing human rights instruments, should be similarly protected online.

The commission called on states to review their legislative frameworks to remove discriminatory laws that increase violence against women online to ensure better protection and “criminalise digital violence against women under domestic national laws”

Given the extensive research conducted on contextualizing the various forms of online gender-based violence in Africa, this resolution represents a significant step towards addressing the issues. Still much more work needs to be done to ensure that the frameworks and national-level policies designed are intersectional and inclusive. Similarly, the implementing bodies need to be proactive and do not further harm groups who do not fall under the normative gender binary. Regardless, we celebrate this major step forward.

Interesting Read On Closing the Digital Divide: Community-Led Projects

Author: Astha Rajvanshi

Astha Rajvanshi is an independent journalist based in Mumbai, where she writes on gender, marginalized communities, and human rights across India and South Asia. Recently, she was awarded the Matthew Power Literary Reporting Award by New York University. As part of her reporting in India, she is currently examining tech surveillance and internet shutdowns. Previously, she was a Fellow for the Institute of Current World Affairs in Washington DC. She has also worked for the New York Times Magazine and Reuters in New York. She was born in New Delhi and raised in Sydney as a proud daughter of immigrants.

Asia Regional Brief

Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders in Asia

The American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative (ABA ROLI) is hiring for the following positions:

A Digital Rights and Internet Freedom Expert for a senior-level, long-term consulting assignment based in East Asia, with a preference for Singapore or Taiwan. Find out more and apply here.

Senior Program Officer in Asia to assist with the development and programmatic support of ROLI programs in field office in emerging democracies and transitioning states. Find out more and apply here.

Access Now is hiring for the following positions: a Digital Safety Specialist in South East Asia, an HR/Ops Coordinator in the Asia-Pacific, and an Asia-Pacific Policy Associate. Find out more and apply here.

The Racism and Technology Center is seeking to fund and support 3 project ideas. Funding for each project is €4,000 for 100h of work over 6 months. The deadline to apply isOctober 31st. Find out more and apply here.

Emerging Topics on Digital Justice in Asia

A look at the #MilkTeaAlliance: How does the humble cup of tea unite digital defenders?

It’s been two years since an online spat between a Thai celebrity and Chinese nationalists over the sovereignty of Taiwan led young social media users to form a new, internet-based political movement dubbed the “Milk Tea Alliance”, named after the popular, unifying drink in these countries.

This alliance, which spans multiple countries across Asia, has since become a community network where people seek out support and share tactics to fight against the threat of authoritarian regimes in their own countries, as well as the overarching threat of the Chinese Communist Party.

Although the effectiveness of the Alliance has since been questioned by some digital experts and activists as a hashtag trend that originated on Twitter, it’s undeniable that even in 2022, the movement can be revived and its reach can have ripple effects.

In early August, when the US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan, Beijing officials were enraged and retaliated by conducting several days of military exercises to intimidate Taipei. Members of the Alliance quickly jumped on Twitter to express their solidarity to Taiwan, describing China as “West Taiwan” or “North Hong Kong” and sharing doctored images of the Chinese President Xi Jingping as Winnie the Pooh.

The hashtags #MilkTeaAlliance, #ไต้หวัน (#Taiwan) and #TaiwanIsaCountry began trending on Twitter, especially in Thailand. At the same time, it also saw clashes between Chinese netizens and sympathizers with Taiwanese independence struggles in the region. In its appreciation, the Taiwan Digital Diplomacy Association tweeted an illustration of the Milk Tea Alliance to thank Thai netizens for showing solidarity against the One-China policy.

In the past, the Milk Tea Alliance has also brought attention to atrocities in Myanmar and youth-led protests in Thailand by amplifying the hashtags #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar and #WhatsHappeningInThailand, while more recently, activists in Iran reached out to the Alliance for support: “Dear friends of the #MilkTeaAlliance, #Iran needs your informational support. The government of Iran supports fascist dictatorships in Russia and PRC, supports the junta in Myanmar! Bring your attention to the protests in Iran! #SupportIranianWomen,” read one tweet.

Experts argue that these online activities between pro- and anti-China netizens should not be dismissed as trivial internet fights. Leading social movement scholars Erica Chenowth and Zeynap Tufekci have noted that the digital playing field is tilted toward authoritarians, and since the #MilkTeaAlliance originated, the political situation in their countries has remained dismal or even worsened.

… young people are among the groups considered most exposed to “threats, harassment, violence and other forms of human rights violations because of their age and the nature of their civic engagement.

At the same time, for members of the Alliance, the impact is clear. Eden, an artist originally from Hong Kong who moderates an Alliance discussion forum via Telegram told Devex that during critical periods, the Alliance ensures news is “spread like wildfire, providing a channel for activists and world politicians to communicate through”.

Thai academic Wichuta Teeratanabodee at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore has also researched the social reach of the Alliance. “Instead of seeing a movement as just a group of people calling for something, I think we should see it within a broader context,” she said. “You’re trying to gain supporters, and you’re trying to educate people. Of course it is a hashtag, but when that hashtag trends online others can read and see what is happening and what the protestors are talking about. It is a kind of pedagogical arena for people to learn about different issues in different countries.”

Using the Internet to Organize

And while human rights and pro-democracy activism is not new, the Milk Tea Alliance’s use of the internet to organize and inform, especially by younger defenders and during the Covid-19 pandemic, has certainly been different. This means that the threats they face are also unique.

According to a 2021 report commissioned by the United Nations Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth, young people are among the groups considered most exposed to “threats, harassment, violence and other forms of human rights violations because of their age and the nature of their civic engagement.”

This can include online surveillance, censorship, and repression alongside sophisticated hacking — such as infecting activists’ phones and laptops with spyware — and is usually followed up with offline attacks. The risk of digital attacks could be enough to undermine activism efforts, according to the 2021 “Ground Safe” report. Digital safety is critical to sustaining activism and so, here are some that human rights defenders could improve their digital safety, as listed in Devex:

Engage in practical training: Totem Project and Tactical Tech’s Digital Enquirer Kit have good HR violation documentation tools. Open Briefing’s Holistic Security Toolkit and the Digital First Aid Kit are useful resources. CCIM has also established a digital rights working group, which runs workshops on digital rights for CSOs, while the nonprofit Security Matters provides digital safety training alongside real-time assistance via a helpdesk for those in Thailand and Malaysia.

Collect data on threats: Record all types of threats and attacks, including the hacking of digital communications, websites, social media accounts, and the use of digital surveillance. If more data is available, it will increase awareness and could lead to increased investment into tools for activists and defenders to better protect themselves.

Continue pushing for accountability: We need more legal frameworks that would allow for the persecution of attacks and threats to be implemented. CCHR is part of the ASEAN regional coalition to #StopDigitalDictatorship in Southeast Asia and denounces rights violations taking place in the digital space and provides recommendations to uphold online freedom of expression and privacy rights.

Finally, we’re left with the more fundamental question: Why do protesters still tap into digital activism and what does it offer activists under authoritarian regimes? As Maggie Shum explained, while the initial commonality shared by the Milk Tea Alliance was a frustration around Beijing’s assertiveness in the pan-Asian region, today it provides an impetus in cultivating a pan-Asian solidarity and has the potential to reshape how citizens can forge a collective pro-democracy consciousness. And that’s what we’re seeing. Even here in India, on Taiwan's 109th National Day, posters that read “Taiwan Happy National Day” were put up near the Chinese Embassy by the ruling party Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) spokesperson. Soon, they had gone viral on Twitter, joined by a meme tweeted by Indian netizens in support of Taiwan. That’s pan-Asian solidarity.

Community News in Asia

The Central Asian community recently mourned the passing of beloved and respected Kazakh disability rights advocate, Veniamin Alayev. Veniamin had recently spoken at #RightsCon 2022 on a panel dedicated to #InternetShutdowns and the rights of people with disabilities.

The Asia Centre, in collaboration with @EngageMedia and supported by @ICNLAlliance, launched their report "Thailand Computer Crime Act: Restricting Digital Rights, Silencing Online Critics" in June. Read the full report here https://bit.ly/3tpqFuJ.

Activists online have expressed solidarity with @DigitalRightsPK's @nighatdad and condemned the online violence she and her family have experienced.

Regional News & Updates in Asia

Activists fear rising surveillance from Asia's Digital Silk Road: This Reuters report notes how Cambodian rights activists say they are under constant surveillance, with their every move online and offline tracked by software, cameras and drones. Much of the technology is supplied by China, which sells extensive digital surveillance packages to governments under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure project.

50 million Indians geotagged their homes for the Indian government: This report in Rest of World noted how a BJP political campaign encouraged people to upload their selfies and locations on India’s 75th Independence Day, alarming digital rights activists over the collection, and potential misuse of citizens data.

Flooding in Pakistan has caused national internet shutdowns: This report in Reuters notes how the largest flooding in the country’s history has also led to a breakdown in communications infrastructure and access to the internet being revoked.

Author: Úrsula Schüler

Úrsula Schüler was born and raised in Chile, South America, where she studied Journalism and worked in media and various organizations for seven years. Spanish is her first language and years ago she was a student representative in high school and her university. After this, as a journalist, she reported two presidential and legislative elections for national media in Chile. She worked in newspapers, a television channel website, and internal communication for universities and companies. Currently, she is studying a postgraduate program in Digital Media Marketing, in Toronto, Canada.

LATAM Regional Brief

Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders in LATAM

Call for contributions to the 1st Online Congress of Popular Education and Free Technologies, which will take place from October 17th to 21st.

Derechos digitales is inviting organizations or activists with no formal affiliation who are working locally on digital rights issues in Latin America to pre-register and submit their applications to the Rapid Response Fund for the protection of digital rights in Latin America (FRR). Pre-register here and make project proposals here.

Mentorship Program for IT Women is looking for individuals to apply for their program which promotes women’s professional development, who are from the internet technical community in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The 15th edition of the Latin American and Caribbean Internet Governance Forum (LACIGF15) will be held between October 24 and 26, 2022. The event, which serves as a preparation for the Global Internet Governance Forum (IGF) will have an online format.

Emerging Topics on Digital Justice in LATAM

Loan Apps: from personal data’s lack of protection to blackmailing users with private photos in exchange for payment

Have you ever asked for a loan from a bank or other financial institution? Have you ever had problems with paying off? Have you heard about loan or credit digital applications which are downloaded on cell phones for money requests, while they access user photos, conversations, and contacts? Well, this is happening and although it can relieve people from urgent cash necessities, some of them deploy totally abusive digital practices for getting users to pay back the funds.

The applications to request personal loans are usually apps that offer micro-loans, ranging to the equivalent of $50 to $100 USD, with immediate delivery and without too specific requests and intermediaries. They gained popularity in the working-class population due to difficulties in getting formal bank credit. In return, the user agrees to pay the amount in a short period of time (5-7 days) with a very high interest rate. This is happening in different countries around the globe. Here, we will review the case in Mexico.

The apps are mainly found in the Google Play Store, but have also been detected in the Apple Store. However, some of them can only be installed outside of app stores and require the user to download the Android Package Kit (APK) file from an external website. Users have been increasingly using these loan apps in the past years and can find tutorials on how to use them. In some cases, the tutorials also come with warnings about possible scams.

Having all this on the table, we talked to Pepe Flores to better understand the problem and think about what we can do about it. Flores is a Mexican digital rights activist, director of communications in R3D, and president of the board in Wikimedia Mexico. Pepe Flores explained that, “These applications are very popular because the bankarization rate i.e. how many people are formally in the banking system and able to access credit in Mexico, is low. Since most people do not have access to loans through financial entities such as banks or through the use of credit cards, they prefer to use these loan systems, especially for amounts of money that are relatively small”. He gives us more details about how these apps work and the illegal practices that threaten people after being late in their payments.

Q: Pepe, what risks have you seen in Mexico for the users?

Pepe Flores: There are serious risks for users. First of all, apps get almost unrestricted access to various permissions of the device they are installed on, including the address book or photo gallery.

These applications have a similar modus operandi: to force the person who received the loan to pay their debt, they resort to blackmail and extortion. This can be done through a bombardment of messages to their relatives and close people, defamation messages even accusing them of criminal activity such as pederasty, intimidating calls, among others.

Q: Has a specific case caught your attention which could depict the situation?

PF: Of the cases that I have had the opportunity to follow, for example, I remember a person who was defamed for child abuse through Facebook Messenger with her contacts. In another case, the app accessed his address book and sent bullying messages to family and friends.

Beyond that threat, there is no clarity in the data usage and cancellation policies, so the risk is not exhausted when the debt is settled. The company remains in possession of these data and can market or transfer them to third parties without any type of control.

Q: What solutions do you see for this kind of situation? Improving the regulation? Setting more requirements for its use or distribution?

PF: First of all, there is a responsibility of the application stores to improve their filters to prevent this type of apps from spreading through these spaces. When a person resorts to a lending app that must be installed outside the official app store, at least they have the notion that they are taking a risk, but when the app is on a site like the Google Play Store, the user trusts in the app being legitimate.

App stores must ensure that no app asks for access permissions disproportionately. That should be the first red flag. If an app wants to access the address book or photo gallery without justification for its operation, a filter should be set. Otherwise, the user is basically opening the door to malware on their device.

In the second instance, the data protection regulation must be applied more rigorously. The policies of use of these applications give an open letter to access, collect, preserve and transfer data without people being able to do anything about it. There is also a lack of creating awareness so that people are informed better which enables them to effectively exercise their data protection rights.

Community News in LATAM

Latin American initiative “No Minor Futures” promotes fairer digital futures with and for children

#NoMinorFutures inspires key stakeholders to co-develop solutions with children and adolescents for better digital futures. The initiative is a global education campaign supported by Mozilla to highlight the values, needs and interests of adolescents related to digital technologies and Artificial Intelligence.

It has global reach but started as a Latin American project by JAAKLAC. For example, No Minor Future showcased an animation story created by a teenage Colombian group - check out the Story of Luisa Juliana. They also co-facilitated a workshop with Jamila Ventorini from Derechos Digitalesabout Artificial Intelligence and privacy, where they talked about the lack of personal data protection and Hours Project, which tries to predict teenage pregnancy and school dropout by young girls from vulnerable communities in Argentina.

Share, learn and do with the support of their multimedia resources created in collaboration with young people and organizations from around the world.

Conexo published step-by-step guidelines for common digital safety tools

Guidelines on topics like password management, two-factor authentication (2FA), secure internet browsing, encrypted email, secure messaging, cloud encryption, disk encryption and others were published in Spanish by Conexo.

This material is now available for trainers, civil society organizations, and independent media. Check here for more information and download links. If you have any comments you can reach them via email: materiales@conexo.org

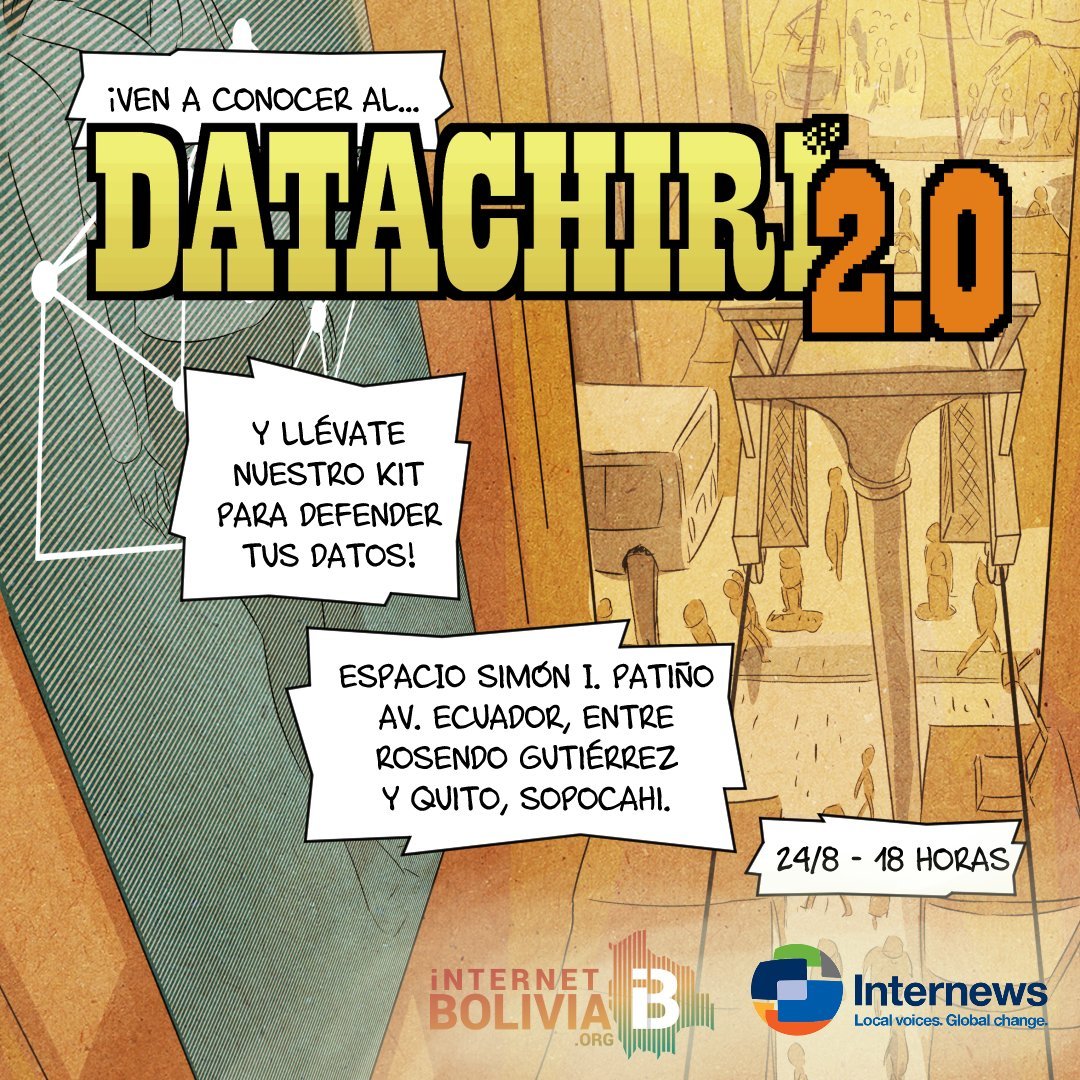

Internet Bolivia promotes a personal data protection law

Bolivia is one of the few countries in Latin America that does not have legislation in personal data protection. In response, the InternetBolivia.org Foundation is working with civil society groups to promote a law to protect personal data with Bolivian authorities on national and subnational levels.

They began searching for different artistic expressions to communicate the importance of having this law. With the comic artists Alejandro Barrientos and Joaquin Cuevas, they created Datachiri 2.0 Comic. It is a dystopian story that shows what happens with our data and our own bodies in 2044 when the personal data protection law would be absent.

In addition, their Digital Economy area held a panel called "The Future of Work in the Digital Age" that sought to reflect on the situation of work and labor rights in the context of platform capitalism. In October, they will present two policy papers on Fintech and Taxes with the aim of generating public policy proposals in Bolivia for the development of the digital economy, led by Hugo Miranda, the Digital Economy officer at Internet Bolivia.

More than 35 human rights organizations are demanding to stop the massive collection and exchange of biometric data in migration contexts.

#MigrarSinVigilancia Campaign - Migrating without surveillance is a human right

More than 35 human rights organizations are demanding to stop the massive collection and exchange of biometric data in migration contexts. This year in May, they sent a letter to Amazon Web Services (AWS) asking for the termination of its agreement to host the Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology (HART) database of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

HART is a biometric database powered by military technology, which will be used to collect large amounts of data on migrants, and exchange this information between the United States and countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, among others. HART promises to host sensitive information from millions of people including facial recognition, iris scans, fingerprints, voice recordings, and more.

They have not received a response to their demands yet and are now running a campaign on social media titled #MigrarSinVigilancia.

Latin America Meetup hosted by TCU

TheLatin America Meet Up hosted by TCU was held on the 21st of September. Read Notes.

Regional News and Updates in LATAM

Apple to appeal Brazil sales ban of iPhone without charger

The Brazilian Justice Ministry fined Apple with 12.275 million brazilian reals ($2.38 million USD), ordered the company to cancel sales of the iPhone 12 and newer models, in addition to suspending sales of any iPhone model that does not come with a charger.

This sales ban order the ministry argued that the iPhone was lacking an essential component in a "deliberate discriminatory practice against consumers". However, Apple said it will appeal the order.

Argentina - court paused facial recognition

On September 7th, a Buenos Aires’s court agreed to suspend use of facial recognition systems in the city. This is a consequence of a legal complaint filed by the civil society organization Observatorio de Derecho Informático Argentino (ODIA), which warned that the security measures, as implemented by a private company, "were not preceded by a profound debate about the relevance and security of the system".

Read more about the case here.

New Chilean Constitution was rejected in the middle of fake news accusations

On September 4th, Chilean people voted via plebiscit about a new Constitution proposal and it got rejected by 62% of the voters. The proposal was elaborated by an elected constitutional convention, after demonstrations in 2019 forced the government to create a new Constitution supporting democracy. The current Chilean Constitution is still an artifact from the times of the Pinochet dictatorship.

The proposal included aspects on digital rights, which generated transversal support. The text incorporated personal data protection rights and the installation of a Personal Data Protection Agency as an autonomously acting institution, among other initiatives.

Analysts have been reflecting on the reasons for the defeat. They found the proposal seems too abstract for the population and the constitutional representatives’ behavior was also criticized. The economic inflation and the criticism the Government is currently facing also affected the vote. The obligatory voting, which called in 85% of the population, showed a “silent” and unexpected opposition.

They found the proposal seems too abstract for the population and the constitutional representatives’ behavior was also criticized.

Another important factor was the online information campaigns targeting voters. Before, during and after the plebiscit, several controversies and digital campaigns related to the proposals' content were running on social media. This article of La Bot Constituyente addressed some of the main points related to the proposal. In addition, the application PubliElectoral for monitoring with Derechos Digitales the advertising investment of the campaign, also generated research about this topic.

CiperChile reported that at least 29 social media accounts invested approximately US$120,000 on Facebook and Instagram to spread fake news on retirement funds, people’s real estate properties, subsidized private schools, and health care stating that they would be at risk with the new Constitution proposal.

In addition, Bot Check Chile showed on several occasions how bots intervened on Twitter for creating artificial Trending Topics or spreading disinformation on social media related to the Constitution proposal. They defined themselves as “engineers at the service of transparency”. They show how bot agencies manipulated opinion on Twitter by generating artificial TTs”. Check this interview for knowing more about them and their initiative.

Elections in Brazil and digital campaigns

Brazilians elect the President, Vice President, and the National Congress on October 2nd. Prior to the election, entities asked the Superior Electoral Court for clarification on a project-pilot that includes biometrics in ballot tests. Check this news for more details.

In addition, Twitter Brasil launched a campaign for preventing misinformation during the election asking users,“Did you fall into misinformation by mistake? It happens. Here's how to fix it”. They wrote to give advice about how to stop spreading fake news on Twitter.

Data Privacy also denounced mass messages in São Paulo, although it was banned by the Superior Electoral Court in 2019. According to Data Privacy, the then pre-candidate for state government, Rodrigo Garcia used messages without the consent of voters, violating current electoral rules. Sent between July and August 2022, the messages made advances in advertising and processing of personal data without the consent of the holders. Read more here.

...

Author: Islam al Khatib

Islam al Khatib is a Palestinian feminist born and raised in Beirut. She researches feminism(s), hegemonies in the 'technocene', ecologies, and grief. She holds BAs in Political Science and Philosophy from the Lebanese University (LU). She is currently pursuing a masters in Gender, Media and Culture at Goldsmiths, University of London.

MENA Regional Brief

Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders in MENA

Bread and Net attendee registration is open. Deadline for registration November 1st: Bread&Net is an annual unconference that promotes and defends digital rights across Arabic speaking countries. It is a great space for networking, learning and being up to date with regional news. Registration by 1 Nov is required for everyone attending the event in-person or online. To register, click here.

IHS MENA Scholarship Program (MSP).Deadline October 9th: The MENA Scholarship Programme (MSP) provides full scholarships to professionals from ten Middle Eastern and North African countries to attend short courses in the Netherlands.The primary goal of the MSP scholarships is to aid in the democratic transition of the selected countries. It also aims to increase organizational capacity by allowing professionals to participate in short courses in the Netherlands. To apply, click here.

Short survey on the internet and digital security in SWANA. Deadline October 1st: This is a short survey for Tactical Tech’s "Data Detox Kit" project to measure the freedom of using the internet and digital security in Southwest Asia and North Africa (SWANA). To fill out the form, click here.

Emerging Topics on Digital Justice in MENA

Mo, Netflix and the Question of Representation & Censorship

Earlier this month, Egypt joined Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar in demanding that Netflix remove content that violates societal values, without specifying what those values are exactly. However, in light of recent homophobic campaigns online and in state media, it is clear that this is essentially about broadcasting LGBTQ+ content that is widely accessible to the public, as if those realities only exist on a screen, and if they are banned from the screen, they are no longer real. Netflix is yet to comment.

To avoid inflaming “regional sensitivities' ', Disney announced in August that it would not stream "Lightyear' ' or "Baymax," two series featuring LGBTQ+ characters on the Middle East version of Disney+, its streaming service. Disney has also stated that it will only broadcast content that complies with local laws.

In May of this year, Netflix issued an internal memo stating that they will not "censor specific artists or voices" even if employees consider the content "harmful," and bluntly states, "If you'd find it difficult to support our content breadth, Netflix may not be the best place for you”. However, the same streaming service, following requests from the Communications and Information Technology Commission, Netflix censored an episode of Patriot Act starring Hasan Minhaj in Saudi Arabia in January 2019, citing material critical of the country such as Mohammed bin Salman and the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen. In a February 2020 report, the company stated that it complied with 9 government-requested content takedowns in various countries, including Saudi Arabia.

This month also saw the release of the Netflix series "Mo," which tells the story of a Palestinian man trying to make a living in the United States. The series sparked numerous discussions online, particularly on Twitter, about representation and who the show is aimed at. The question of the audience becomes central once more in a very different conversation.

Despite the differences in context of the examples highlighted, it is clear that the issue of censorship and what to screen is becoming central in discussions about streaming services and their need to respect what is often referred to as "local cultures”.

When discussing representation and censorship on streaming services and similar companies, however, there is a contradictory position. Many people argue that the works that Netflix airs, for example, promote and publicize the Israeli Mossad and glorify the heroism of its agents who have committed dozens of extrajudicial killings - the documentary series Inside the Mossad is nothing more than pro-intelligence propaganda. Not surprisingly, this leads many folks to be sceptical of what Netflix presents to their audience as "true Palestinian experiences”.

Between companies looking to profit and governments looking to control, the issue of representation and censorship becomes extremely delicate and fraught with other concerns. This includes the fact that censorship seeks to erase all traces of dissent, and that hypervisibility may endanger people or lead to misunderstanding or misinterpretation of a lived reality.

This conversation is especially relevant to MENA digital rights defenders because it addresses questions about methods and censorship: fighting censorship does not necessarily imply embracing any given form of representation, but rather questioning the idea of having to choose either/or from the start.

In an increasingly violent environment, it is critical to start a conversation about how to fight censorship, knowing that authorities use it to control discourse but also to fragment people and pit them against each other in a never-ending battle for a "true" representation of who they are.

Regional News and Updates in MENA

Feminists in Iran and beyond demand justice for Jhina Amini (the Kurdish name for Mahsa Amini) in the Midst of Internet Restrictions

Following the killing of Jhina Amini (22) by the Iranian morality police for not properly wearing the hijab, protests in Iran erupted led by women demanding justice and an end to this control over women's bodies. Authorities have attempted to obscure the truth, first by denying that the murder occurred, and then by releasing clearly edited surveillance videos from CCTV cameras rather than the morality police's bodycams. Following the outrage by feminists, the head of the morality police has reportedly been suspended from his position.

On September 21, Iran experienced its most severe internet restrictions since 2019, with mobile networks largely shut down and Instagram and Whatsapp severely restricted. Feminist activists have also reported that their content, particularly that which documents violations, has been removed. On Wednesday 21 September, Instagram, one of Iran's last remaining social media platforms, was blocked by all major internet providers. Earlier this year, in June 2022, a group of Iran-based feminists sent a letter to Meta regarding an unprecedented attacks on Iranian feminists accounts that have a large following on Instagram and Facebook. Meta has yet to respond to or address these concerns.

Google, Labor Rights and anti-Palestinian Rhetoric

Google has once again come under fire from both pro-Palestine activists and digital rights advocates. Following the #NoTechForApartheid campaign - led by Palestinian and Jewish Google and Amazon employees protesting a 1 billion contract which will provide Israeli government and military with artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, and signed by over 700 Google employees concerned about how this will increase human rights abuses in the Palestinian occupied territory and beyond - the tech giant is retaliating against its employees.

Ariel Koren, a Jewish employee resigned via a public letter due to this retaliation, and states that coworkers protesting Project Nimbus are being silenced across the company, receiving HR warnings, harassment, even pay cuts and negative performance review feedback.

This case is multilayered, involving labor rights and diversity, and also the issues of tech companies pursuing military contracts.

Image’s source: Wikimedia Commons.

Koren claims that Google's DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) policy did not prevent retaliation against women, queer, and BIPOC employees. Being fired or forced to resign because of an individual’s politics is not new, and has been a central challenge to labor rights movements for over a century. However, politics in the Google context means not only expressing opinions, but also protesting violent policies and refusing to be complicit, which is obviously not covered by most employment protection laws. In addition, in the letter Koren discusses how Google has used "diversity" to create groups and spaces for people with "shared or common identities," and how this has become a form of driving right-wing policies at the company.

Project Nimbus is a 1.2 billion military contract between Amazon, Google and the Israeli military and government. The agreement provides Israeli authorities with artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud storage services which will increase the use of digital surveillance in occupied Palestinian territories. In addition, the project contractually prohibits Amazon and Google from suspending services to specific Israeli government entities, such as the Israeli Defense Force, even in response to boycott pressure.

According to a trove of training documents and videos obtained by The Intercept, the new cloud will give Israel capabilities for facial detection, automated image categorization, object tracking, and even sentiment analysis that claims to assess the emotional content of pictures, speech and writing. In addition, trainings will be made available to government personnel through online learning services Coursera, citing the Ministry of Defense as an example.

Over 750 Googlers and over 400 Amazon workers have called on Google to drop Project Nimbus at go/drop-nimbus. They have also been protesting in front of the headquarters and main offices across the US.

Project Nimbus is not occuring in silence or without protest, which is why Ariel Koren and others are calling on digital rights defenders to join the fight.

During a recent Team CommUNITY Glitter Meetup on September 22, Alice and Laila from the European Legal Support Center (ELSC) discussed the digital panopticon on pro-Palestine content in the digital sphere, and the ways in which this leads to self-censorship, as well as the need for digital rights defenders to create an infrastructure in which people are allowed to speak freely.