October 2022 | Digital Rights Regional Briefs

Danae Tapia, Global Community Manager & Resident Hechicera

Here’s a new release of our regional briefs!

This is the place to find updated and critical information about digital justice issues around the globe. Focusing in the Latin America, MENA, Africa and Asia regions, our reports cover Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders, Emerging Topics on Digital Justice, Community News, Regional News And Updates.

I personally recommend taking a look at the topic of the Guacamaya hacking leaks in Latin America.

Please contact us if you know about individuals or groups working on issues that should be reported in our briefs. Our intention is to adopt innovative perspectives away from mainstream discourses, and consequently, promote a more heterogeneous digital rights space.

Danae

Global Community Manager

Asia Regional Brief

Africa Regional Brief

Latin America Regional Brief

MENA Regional Brief

Author: Mardiya Siba Yahaya

Mardiya Siba Yahaya is our Africa Community Lead. She is a feminist digital sociologist, researcher , learning designer and storyteller whose work examines the internet and its cultures from the margins of gender and location. She has a Global Challenges degree from the African Leadership University, was awarded the Mandela Rhodes Scholarship in 2021, and is currently awaiting her Masters Degree in Sociology from the University of the Witwatersrand.

Africa Regional Brief

Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders

Mozilla is seeking applicants for its third data futures lab cohort.

Association for Progressive Communication is hiring a project administrator.

Open Archive is looking for a Project Coordinator

The UN Women Africa Youth Steering Committee is accepting applications.

Apply for TechGirls, a summer exchange program for young women from around the world called aims to empower and inspire them to pursue careers in science and technology.

Emerging Topics on Digital Justice in Africa

Trends on Online Violence, Moderation and Policies We Need to Paying Attention To

Conversations surrounding online violence, harassment, and abuse are not in any way newly emerging. There is continuous work from digital rights communities to improve content moderation and social media governance policies. In this month's brief, we explore the dichotomies of private versus public regarding online gender based violence, safety, and moderation.

A Case Study from Ghana: Trigger Warning - Violence

Illustration: Kelsey Borch via Shameless Mag.

In August, a group of women on Twitter shared their experiences of abuse by one of the owners of Afrochella (social media handle @deezydothis) who would share his unsolicited nudes, and explicit images in their Snapchat direct messages. SnapChat’s affordances are designed for people to communicate using pictures in the form of ‘chats’, which expire after 24 hours or longer when the receiver decides to save the chat. Snapchat is very popular among young people in Ghana and can be a conversation starter where people create Streaks and more.

The experiences of abuse and harassment the women shared on Twitter demonstrates the gendered affordances to Snapchat’s design. To understand the situation, we spoke with a person who experienced and witnessed similar forms of abuse online to further understand the situation. To protect her identity, we will refer to her as Rija.

Rija’s Story

Snapchat is very popular among young people in Ghana.

Rija explained that the culprit the women were speaking of had also abused her friends, who consented that their stories be shared by her. Rija shared that this began in 2020. Once they add the abuser to their Snapchat, he would share his unsolicited images and nudes within a few hours. Rija also experienced this form of abuse in her direct messages by different individuals on SnapChat, Instagram, and Twitter. When experiencing this abuse in the form of over sexualization, unsolicited nudes, and sexualized verbal abuse, Rija shared that she deleted all her pictures from Instagram, began to only use her private SnapChat account, and burner on Twitter. When the abuse in her direct messages increased, she took a full break from social media during Ramadan.

Complicating Matters: Public vs Private Spaces

When a user posts on their public feed, it is considered as some-what ‘public’ information. Engagements in the DMs are typically categorized as private. What distinguishes SnapChat’s affordances from most social media is that it mostly relies on what we may refer to as a private engagement between individuals.

Illustration by Noa Denman.

Most content moderation currently focuses on the public aspect of violence. When we asked Rija if she had encountered options to report a DM, she said she had not seen an option, but was mostly encouraged to block the account when she reported it. For example, Rija shared that the first time she spoke about sexual violence on a Twitter space, she received DMs from men who would tell her “I like your voice, can you speak to me while masturbating”. Rija wondered how she would be able to report these accounts. Twitter would ask her to share the specific ‘public’ tweet that was in violation. Given that this experience was not public, she could not directly report a DM.

Based on this story, we did our own research. Twitter and SnapChat indeed do have options to report a direct message, but it is quite difficult to find because it is either lumped into other reporting categories.In the case of SnapChat, users might spend a lot of time searching for their support center on the app. Yet, moderation remains subjective and when the platform is unable to ‘verify’ abuse in whichever way they define it, they suggest users to block the account in concern. Unfortunately, this is not a sustainable strategy for a safer environment: Rija’s abuser is back on Twitter after taking a hiatus and his SnapChat account still exists despite multiple people reporting him.

Consequences after the reporting?

Abusers’ understanding of how ‘public’ and ‘private’ spaces work also allows them to opt to harass and violate women through the DMs because it would require extra effort to hold them to account.

The experience provides a view into how gendered violence and abusers utilize the power and complication between public and private space. For instance, in our offline world, many would invoke the concept that people should stay out of ‘private’ matters even when abuse and violence is occuring. This is sometimes also a reaction to intimate partner violence where peers feel they do not want to ‘overstep’ their boundaries. On the other hand, these responses and concepts do not change even when violence is happening ‘publicly’, either because of fear or complicity.

On SnapChat and Twitter, we are also seeing that these social organizations and conceptions of violence are governing how the platforms are designed and moderated. Abusers’ understanding of how ‘public’ and ‘private’ spaces work also allows them to opt to harass and violate women through the DMs because it would require extra effort to hold them to account. In Rija’s example, it took the women three years to identify this ongoing abuse before organizing and coming together to name them as abusers.

In other words, there are no consequences for gendered violence or abuse online and offline. For Rija, there needs to be a balance between how people can report violence that happens in a supposed private space. She leaves, ‘how many people need to report an account for the platform company to acknowledge it?’ There needs to be direct consequences for people like Afrochella co-owner to hold them accountable: they should not be able to simply get away with sexual violence’.

Community News in Africa

Queering the Internet: Rightify Ghana is Documenting Experiences and Supporting LGBTQI+ Ghanaians

Perspectives on ‘queering’ the internet enables us to consider how we can center alternative strategies to enable people of different genders and sexuality to safely use digital technologies at its fullest potential. This means addressing violence at all intersections. However, queering the internet relies on some offline liberations, which is also being advocated for by rights groups Rightify Ghana.

Rightify Ghana is a non-profit organization established in 2020 to deliver high quality programmes and services that empowers LGBTQI+ persons through advocacy, human rights education, personal development activities, counselling, mentoring, and community support activities. Their vision is “to ensure a society that celebrates diversity and acknowledges the dignity of marginalized and vulnerable populations as well as embraces full human rights for all people.”

Photo courtesy of Rightify Ghana.

In 2020, Rightify Ghana started documenting the abuses and increasing violence LGBTQI+ Ghanaians face because of the anti-LGBTQI+ bill being campaigned by members of parliament in the country. They also collaborated with key human rights organizations and stakeholders such as CIVICUS to highlight the threats queer Ghanaians face. Rightify Ghana is a support network, has a help-portal for reporting cases, counters disinformation on sexuality and HIV, while also providing reproductive health services and digital safety and security support to communities.

Rightify’s work is not without threats. In August 2020, the director of Righitfy was kidnapped, tortured and held hostage when following up on a reported case, which appeared to be a trap. This is part of the larger threats LGTBQI+ groups in Ghana experience. For example, in May 2021, 21 LGTBQI+ activists in a town in Ghana called Ho were arrested by the police. Law enforcement in the country have also been known to use social media to surveil and track pro-LGBTQI+ activists in the country. In addition to the disinformation and hate campaigns, these threats are designed to incite violence against queer Ghanaians and activists.

How you can support their work: Donate to Rightify Ghana to support their projects, programmes, providing safe spaces for at-risk groups and documenting human rights abuses. You may also contact them to collaborate and build a resilient partnership.

Aumarh One of Our Community Members from RiseUpNet is Supporting One Love Sisters an LBQI organization in Ghana with Digital Security

Aumarh conducts physical, digital and psychosocial risk assessments with One Love Sisters to identify the threats they face and collaborate with the organization to input systems and grow their capacity. Her work responds to the multiple security challenges Ghanaian queer groups continue to face. Aumarh shares that to protect at-risk organizations and communities, the digital rights and human rights ecosystem needs to consider alternative advocacy strategies that do not further harm the organizations and recognize their choices to not be visible in normative aways.

Regional Update

Sudan campaigners are demanding action after the rise in ‘honour killings’: This year, 18 women were killed due to ‘honor killings’. Dafur, a young girl, was murdered by her familiy members who believed she was unmarried and pregnant.

Other women have been killed for supposedly speaking to men on social media. One of the activists leading the campaign against honor killings Nahla Yousif explained that the rise of mobile phones and the use of social media means “more men are unable to feel in control of young female relatives.”

Women activists who conduct field work on documenting the abuse within displacement camps are also being targeted by relatives. According to Yousif, they have had to provide shelter for some of the women activists because relatives believed that since they have smart phones, they will be chatting with men.

These issues also demonstrate the multiple forms of gendered violence that is influenced by the existence of alternative forms of engagement and communication through technology. While women are able to ‘freely’ use certain technologies, the patriarchal push back happens through violence to reinstate fear, thus controlling women’s free expression.

Stand Against Amal's Death By Stoning Sentence: Amal, a 20-year old Sudanese woman, was sentenced to death by stoning for ‘adultery’. In August the government also announced a new police unit. This announcement suggested the return of the “morality police”which punished “immoral” behavior under former president Omar al-Bashir.”

The 20th of October commemorates the second anniversary of the Lekki Tollgate shooting that happened during the EndSARs protest in Nigeria in October 2021. The government continues to claim that the shooting did not happen despite live footage that documented the incident.

Interesting Read: (In)Visible, documenting the digital security threats of Muslim Women Human Rights Defenders in the Horn of Africa.

Author: Astha Rajvanshi

Astha Rajvanshi is an independent journalist based in Mumbai, where she writes on gender, marginalized communities, and human rights across India and South Asia. Recently, she was awarded the Matthew Power Literary Reporting Award by New York University. As part of her reporting in India, she is currently examining tech surveillance and internet shutdowns. Previously, she was a Fellow for the Institute of Current World Affairs in Washington DC. She has also worked for the New York Times Magazine and Reuters in New York. She was born in New Delhi and raised in Sydney as a proud daughter of immigrants.

Asia Regional Brief

Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders in Asia

Project Administrator at The Association for Progressive Communications: The APC is looking for a project administrator to join their virtual office and support the team in the global South-led consortium “Our Voices Our Futures”.

Security Consultant (Myanmar) at The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA): FORUM-ASIA is hiring a security consultant to contribute in implementing strategy and action plan for the HRD Programme in line with FORUM-ASIA’s overall protection strategies.

East Asia Researcher atThe Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project:

The OCCRP is hiring an experienced researcher with extensive knowledge of tracking down public records in China and surrounding countries to support our partners and projects.Policy Analyst (East Asia) and South Asia Advocacy Contractor at Access Now: Access Now seeks a South Asia Advocacy Contractor to aid in devising advocacy initiatives and campaigns to support their position on policy discussions broadly affecting privacy, surveillance, digital security, internet shutdowns and cybersecurity in South Asia. Access Now also seeks a Policy Analyst to be deeply involved in policy initiatives in the East Asian Region (including Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, as well as South Korea, Japan, and Mongolia).

Cyber-security Specialist (Cambodia) at Functional Cybersecurity International:

FCI International is looking to add a team member to the South Asia Team to support current digital and cyber-security activities in Cambodia. The candidate must be based in Phnom Penh.Multiple Positions at TechSakhi: TechSakhi is a digital safety helpline for women and LGBTQIA+ persons run by Point of View, a Mumbai-based non-profit that works on gender and technology. They are hiring for three different positions and looking for experienced persons to help grow their knowledge base in keeping with our ambitions, including a Knowledge Management Lead, a Partnership Lead, and a Marketing Manager.

Communications Associate and Technologist, SFLC.In: SFLC.IN is hiring for a Communications Associate and a Technologist to help their mission to defend the digital rights of Indian citizens.

Pitches for stories for SMEX: SMEX is seeking pitches for stories exploring potential challenges and threats to digital rights in the time period leading up to and during the Qatar World Cup. Read more and apply here.

Emerging Topics on Digital Justice in Asia

An Indian News Outlet Claimed Meta Allowed the Indian Government to Moderate Instagram Posts, Until Its Reporting (very publicly) Backfired. What’s next?

Recently, an explosive report by The Wire, an independent Indian news outlet known for its gutsy and often critical reporting of the Indian government, alleged deep ties between the Bharatiya Janata Party, the ruling party of India, and Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram. But after the social media giant strongly denied the story’s allegations and many readers complained on Twitter about the sources appearing to be fabricated, the outlet took its report down, saying it would review the allegedly leaked documents it relied on for its reporting.

I won’t try to hash out the details of exactly what happened if you’re new to the saga, because several other competent publications have summarized the incident in their reports, including Rest of World, The Washington Post, TechCrunch, and Slate.

And while it increasingly appears to be a case of a story that might have been too good to be true, the incident has revealed one of the most serious lessons in the history of tech journalism: the loss of credibility for any news outlet also means the loss of scrutiny around the extraordinary powers potentially granted, and wielded, by social platforms, especially in polarized political environments.

As Nitish Pahwa wrote in Slate, The Wire’s original story was also a story about India, where the government “has worked consistently to reduce press freedoms, and is working to create a government panel that could review and overturn social networks’ content moderation decisions.” We learnt last year, from The Wire itself, that the Indian government had likely used the NSO Group’s Pegasus software to surveil journalists and other dissident citizens, including The Wire. These findings were confirmed just last week in a damning story by the Organized Crime and Corruption Project, which found trade documents that show India’s domestic spy agency bought hardware from NSO that matches equipment used to deploy Pegasus in other countries.

The Organized Crime and Corruption Project found trade documents that show India’s domestic spy agency bought hardware from NSO that matches equipment used to deploy Pegasus in other countries.

What’s less clear are the answers to a few important questions initially raised by The Wire’s reporting about Meta’s content moderation practices:

What are the benchmarks around content moderation used to determine which posts stay up and which posts are taken down?

Are these decisions taken by an automatic computer system, humans, or both?

The Scroll.in, another independent Indian media outlet, raised these questions with Meta’s communications team, who responded by sharing the link to their official statement. It said:

Users with Xcheck/cross-check privileges cannot have content removed from the platform with no questions asked.

Questionable posts are surfaced for review by automated systems, not user reports.

The Wire’s articles are based on fabricated documents and screenshots.

There is no Meta “watchlist” for journalists.

But in India, many posts on Instagram and Facebook remain untouched, despite appearing to violate the platforms’ guidelines against hate speech. Scroll.in’s reporting shows many examples of this, including this one: Facebook did not take down a video of BJP minister Anurag Thakur leading chants of “goli maaron saalon ko” (shoot the traitors) at a rally in North West Delhi’s Rithala in January 2020. “Sala”, which literally means brother-in-law in Hindi, is also used as an expletive. The video resulted in the Indian Election Commission imposing a three-day ban on campaigning by Thakur, but it does not appear to have violated the platform’s guidelines against hate speech and is still available on Thakur’s verified page.

How Much Oversight is Exercised by Meta in the End?

This scrutiny is crucial at a time when we already know, thanks to this 2021 report by The Wall Street Journal, that Meta’s XCheck, or cross-check program, allows high-profile users to avoid Facebook and Instagram content moderation procedures. Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen even claimed in October 2021 that the platform was aware of anti-Muslim posts in India, but took little action because of “political considerations”.

What do we know about how much oversight is exercised by Meta in the end? We know that the Big Tech giant has an Oversight Board that delivers verdicts on contested moderation of posts. This has been hailed as a “one of a kind” measure, though the platform still faces challenges and criticisms for turning in late verdicts and addressing a few posts. In the first quarter of 2022, the board received 479,653 appeals by users and Meta, but only 20 of those user-submitted cases were shortlisted. The platform reversed its decision in 70% of these instances. What’s more, a study by NYU’s Stern Centre for Business and Human Rights in 2020 found that Facebook employs only 15,000 content moderators across the world, while more than 3 million posts are reported for removal by users and AI on a daily basis. Relatedly, Equality Labs also published a report in June 2019 on how memes and posts posted on these platforms target Indian caste, religious, and LGBTQI+ minorities.

Community News in Asia

TCU Asia Regional Meetup will be held on Mattermost on October 28. We will be speaking to MTA Galleries, a child of northern pine forests, living in Asea/SEAsia for over 13 years. For most of their adult life, they have been managing IT-related projects, but object-oriented ontology, Hong Kong protests, and SEA grassroots heavily impressed and inspired them to participate in activism. Follow their work on @MTA_Museum.

The Localization Lab is looking for contributors to do Tagalog translation and review on the Check Continuous localization project. The content will be uploaded on a weekly basis by the developers and they need people who are able to translate and review the content before the next new batch of content is updated. More details here:

Project Wiki page: https://wiki.localizationlab.org/index.php/Check

Funder website: https://meedan.com

Is freedom of expression under threat in South Asia? The acclaimed digital rights expert @nighatdad will be discussing this issue at the 4th Asma Jahangir Conference #AJCONF and sharing solutions to promote human rights & internet freedoms. You can watch the livestream on 22nd and 23rd October @voicepkdotnet.

The 12th edition of Freedom House’s #FreedomOnTheNet report is live. This year, FOTN explores how governments are breaking apart the global internet to assert their control over online spaces. You can read the report here.

In partnership with @gawadalt, @EngageMedia curated a film playlist on @cinemata highlighting human rights stories from the Philippines' martial law years to the present time. Explore more here.

Regional News & Updates in Asia

Big story by @OCCRP: Import data shows that in April 2017, Israel's NSO Group, which makes #Pegasus, exported hardware to India's Intelligence Bureau.

Sick of data leaks, Indonesians are siding with a hacker who exposed 1.3 billion SIM card details. More from Antonia Timmerman in Rest of World here.

In China, AirDrops are the latest tactic in spreading protest messages. More from Rachel Cheung in VICE here.

Author: Úrsula Schüler

Úrsula Schüler was born and raised in Chile, South America, where she studied Journalism and worked in media and various organizations for seven years. Spanish is her first language and years ago she was a student representative in high school and her university. After this, as a journalist, she reported two presidential and legislative elections for national media in Chile. She worked in newspapers, a television channel website, and internal communication for universities and companies. Currently, she is studying a postgraduate program in Digital Media Marketing, in Toronto, Canada.

LATAM Regional Brief

Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders in LATAM

Meta’s 2022 Foundational Integrity Research request for proposals. Deadline: November 22, 2022.

Derechos digitales is inviting organizations or activists with no formal affiliation who are working on digital rights issues locally in Latin America to pre-register and submit their applications to the Rapid Response Fund for the protection of digital rights in Latin America (FRR). Pre-register here and make project proposals here.

Quinto Elemento Lab is calling for investigative journalism projects.

RightsCon presented its topics to watch for their 12th edition in 2023: Gender Justice, Labor, and the Environment.

Community Support Coordinator position available at RightsCon.

Legal Officer (Latin America) position available at AccessNow.

Calling to the II Encuentro Latinoamericano de Antropología Digital: Expandiendo Futuros! (Latin American Meeting of Digital Anthropology: Expanding Futures! in Spanish).

Emerging Topics on Digital Justice in LATAM

Hacking Latin American Armies Reveals Persistent Pegasus Usage and Spying on Activists and Journalists in the Region

At least six countries have suffered some hacking and leaking of sensitive information in Latin America by the group “Guacamaya”. According to their press release, the organization is against Global North’s colonization of the Global South, the extractivism for eroding nature, militarization, and patriarchy. Check this Forbidden Stories interview with Guacamaya for a better understanding of the group's intentions.

Guatemala, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, México and Perú have experienced a hacking series conducted by Guacamaya. The hacks and leaks are called “Repressive Forces” and have exposed documents from the military forces and other key institutions to media and organizations. The files have been analyzed by them and were published in diverse articles.

The hacktivism case revealed a series of digital rights’s violations and also the weak cybersecurity system level in critical Latin American institutions, such as the armies, the justice systems, and some private mining companies. Here we will review some of the main cases in the region.

Guatemala: Giant mining damage

In March, Guacamaya hacked the communication systems of the mining project Fénix, which is managed by the Guatemalan Nickel Company from the mining conglomerate Solway Group. Thereafter, Forbidden Stories published a press report called “Mining Secrets”. Their findings go from “drafting proposals to spread rumors about and ‘buy’ community leaders to transferring money to the national police”.

Colombia, El Salvador and Perú cases

During the 2019 demonstrations in Chile, the Policía de Investigaciones (the Chilean investigative police) was investigating a group that organized poetry recitals and raised money for a literary magazine.

In August, the Guacamaya group hacked five thousand gigabytes of emails belonging to the Fiscalía de Colombia (the Colombian Prosecutor's Office). In the statement published by Guacamaya, they brand the institution as one of the most corrupt in the country.

In the case of El Salvador, Guacamaya has information about 250,000 emails (73 gigabytes) belonging to the Armed Forces of El Salvador (FAES) and 10 million emails (6.8 terabytes) from the National Civil Police (PNC).

In addition, the Peruvian Army suffers the biggest hack in its history: 283,000 emails and plans were revealed in the face of a hypothetical war with Chile.

Chile: Army strategies revealed and police investigation towards activists

On September 19, the”Day of the Chilean Glories of the Army”, about 400 thousand emails from the Estado Mayor Conjunto de las Fuerzas Armadas were revealed. This institution is in charge of working with and permanently advising the Ministry of National Defense on issues related to the joint organization of the Armed Forces in the country.

Among the files leaked by Guacamaya, Resumen found that during the 2019 demonstrations in Chile, the Policía de Investigaciones (the Chilean investigative police) was investigating a group that organized poetry recitals and raised money for a literary magazine.

In addition, the investigative journalism center Ciper found a massive hacking of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, exposing thousands of documents from sensitive defense areas in Chile. The hack of the Peruvian Army revealed Peru’s war plans in case of an attack from Chile.

Mexico: Spy Army and NSO’s Pegasus again

Towards the end of September, the Mexican government confirmed that Guacamaya hacked their Secretary of National Defense (SEDENA), which leaked 6 terabytes of confidential information dated from 2016 to 2022. On October 2nd, R3D, Article19 Mexico, and SocialTIC presented some of their findings related to digital rights among the documents: three new Pegasus spyware attacks on journalists and human rights defenders. They also demanded safety for the people spied on and for those who are involved in the “Ejército Espía” (Spy Army in Spanish) facts investigation.

Pegasus is a spyware developed by the Israeli cyber-arms company NSO Group that can be covertly installed on devices such as mobile phones for surveillance purposes. In this sense, the investigation “Ejército Espía” (Spy Army in Spanish) established that both the Mexican government and the Mexican armed forces are responsible of three new cases of espionage against journalists and human rights defenders in Mexico with Pegasus malware: Raymundo Ramos, President of the Human Rights Committee of Nuevo Laredo; Ricardo Raphael, journalist and writer; and a journalist from the Animal Político media. They also confirmed that the deputy Agustín Basave Alanís was spied on with Pegasus.

The Mexican investigation was supported by Citizen Lab of the University of Toronto, Canada -which made a forensic analysis of the devices- and also the media Animal Político, Aristegui Noticias and Proceso collaborated.

The leaked documents from all these countries are still being analyzed and more media articles about their content are to be released. In this sense, the organization SocialTIC elaborated a guide for handling the leaked documents properly, considering that journalists warned that some files are infected.

We talked with Paul Aguilar from SocialTIC about all this.

Team CommUnity (TCU): What violations of digital rights have you detected in the case of the Guacamaya hacking leaks?

Paul Aguilar: The first thing I would like to clarify is that at SocialTIC, we understand that the hacktivism actions of groups like Guacamayas respond to very specific contexts and generally represent actions of resistance that we admire, but that depending on the same context, they can be illegal and strongly persecuted, for which it is something that we leave to the discretion of each group or person to consider how to take it.

Regarding the leaks corresponding to Mexico, the information has been released little by little to the groups or media that requested it. Given that it is a lot of information, it has taken time for processing and analysis.

Among the main results, the intelligence actions where civil society groups have been identified as high risk groups towards the interests of the government and the groups of power stand out. The links between these groups have also been identified, such as the government, organized crime or private companies (who generally tend to be the aggressor groups of civil society), and lastly very specific issues related to budgets, transparency and corruption of institutions or mega projects within the country.

Although not all of the above is linked to the issue of digital rights, they do have a direct connection with the activism or incident that is carried out in the country and that ends up placing civil society groups as high-risk opposition groups from the perspective of the current government.

The espionage cases only confirm that the digital rights of activists, journalists and civil society in Mexico continue to be violated with tools that are not being transparent in their acquisition or regulated in their use.

TCU: Considering the other cases in the different countries, what challenges for digital rights do you see for the region?

Paul: Regarding challenges in digital rights in the region, we have identified that in other countries, there have been previous negotiations on the acquisition of this type of technology. The clearest case was that of El Salvador at the end of last year where the use of Pegasus against journalists, activists, and civil society organizations was confirmed.

However, there are indications of the use of other types of technologies focused on communications intervention, active monitoring in social networks, and manipulation of speeches on digital platforms.

Even in more local contexts, the most famous example is the use of tools such as Cellebrite's UFED for device information extraction. All this happens without clear mechanisms of acquisition, use, or regulation, which leads to a complex situation of abuse of this type of tool. This puts civil society groups in a vulnerable situation.

Community News in LATAM

Saga Detox de Datos: the Latin American campaign for digital well-being

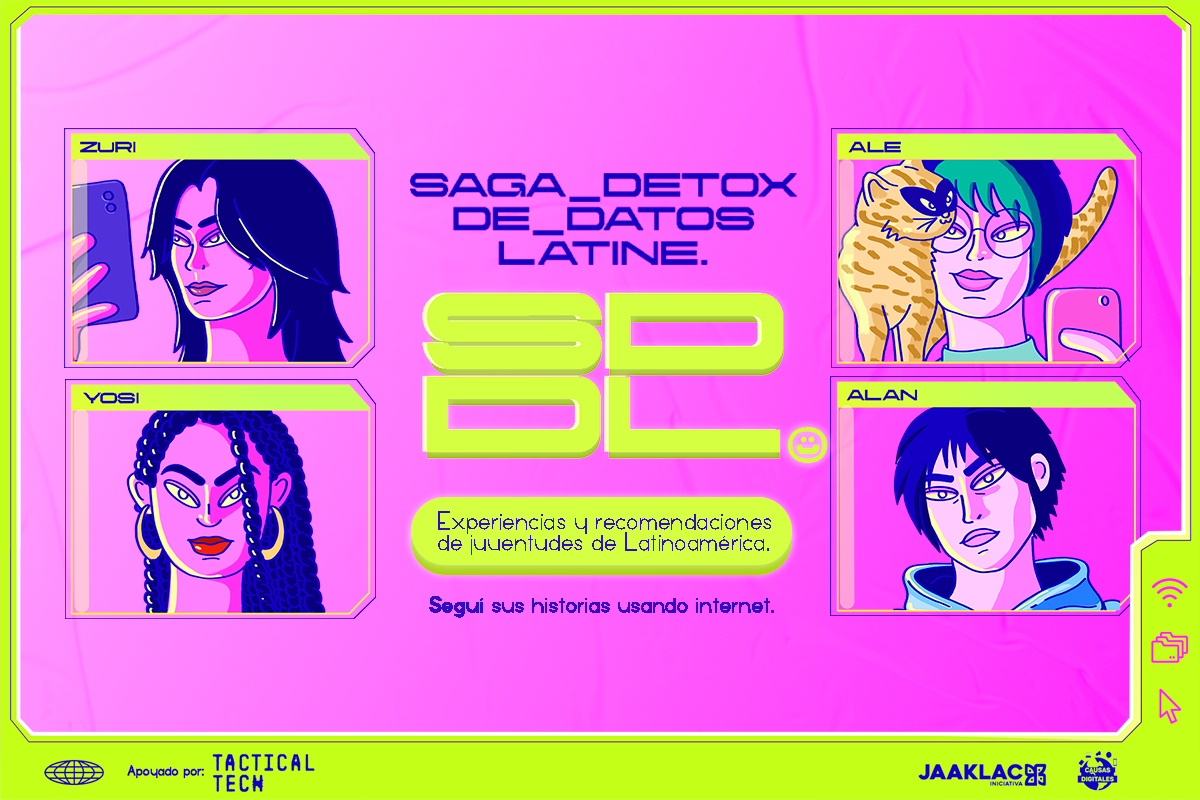

“Did you know that the average person clicks and swipes on their phone more than 2,600 times a day? And you, how many times do you do it?” This is one of the questions related to the Data Detox Saga campaign, which the JAAKLAC initiative is promoting next to Hijas de Internet, InternetBolivia.org, Hiperderecho, Conexión Educativa, schools and youth organisations. The series stands out for digital well-being in our internet and usage of devices, storytelling new experiences and cases created by and for young Latin Americans and providing a kit of measures and habits for detoxifying digital overuse. For example, check here how Zuri from México developed healthier habits.

The campaign adapted Tactical Tech's Data Detox Kit about privacy, safety, and wellbeing to the youth experiences. The result included the resources and backgrounds from Latin American organizations.

New bot on WhatsApp provides guidance on what to do when somebody disappears in Mexico

In Mexico, an average of 15 people disappear every day. Between 1964 and May 31, 2022, there were 100,447 registered missing people in Mexico, of which 83.7% occurred in the last 16 years, according to a study by the General Directorate of Strategic Investigation of the Belisario Domínguez Institute (IBD).

Quinto Element Lab, Codeando México and Técnicas Rudas created "SocorroBot" (Help or SOS Bot in Spanish) on Whatsapp, which offers essential information and recommendations about the report of missing persons, depending on the profile of the disappeared person, the place where the event occurred and from where this is reported.

Comic Datachiri from Bolivia is now in different formats and in English

InternetBolivia.org and the comic artists Alejandro Barrientos and Joaquin Cuevas created the Datachiri 2.0 Comic, a dystopian story that narrates what happens with people's data and bodies in 2044 without a personal data protection law in Bolivia. The comic is now provided in English and is also on YouTube and Spotify.

Cristian León is the Executive Director of the InternetBolivia.org Foundation, an organization that promotes digital rights and digital inclusion in this South American country. Bolivia is one of the few countries in Latin America that does not have legislation in personal data protection. The organization advocated a corresponding law and also searched for different artistic expressions for breaking the technical barrier, while communicating the importance of establishing the law in their country.

Cristian explained the origin of the Datachiri comic idea: “Bolivia, as part of the whole Andean region on this side of the world, is full of myths and traditions. One of them is that of the Kari Kari, a mythological being, who sometimes appears in the form of a foreigner or stranger to the place, kidnaps you and extracts your fat and vitality. It is said that once the Kari Kari appears, your health will deteriorate and you even run the risk of dying slowly. So, we wondered, is there a modern Kari Kari?”.

In this sense, León explained also that “Chiri has different meanings: in Quechua it means ‘cold’, and in Aymara it is more referred to as ‘male’” - both from indigenous languages - and that “Datachiri is a representation of the Kari Kari, a being that is sucking our digital vitality, our personal data.”

Among their other initiatives, InternetBolivia.org also developed a diagnosis of access and personal data in 6 autonomous territorial entities. This document addresses two digital rights that are still a pending issue in Bolivia, and in which indigenous municipalities and autonomies can play a role: the right to access the Internet and the protection of personal data.

Latin America Meetup hosted by TCU

The Latin America Meetup hosted by TCU was held on the 19th of October. You can read the notes of the meetup here.

Regional News and Updates in LATAM

15th edition of the Latin American and Caribbean Internet Governance Forum

The 15th edition of the Latin American Internet Governance Forum (LACIGF15) was held online on October 25 and 26 and included four open sessions. In addition, on October 24, “day zero” was placed with activities by Youth LACIGF and national and regional internet governance initiatives (NRIs).

Derechos Digitales analyzes data privacy in Chile

The non-profit organization Derechos Digitales (Digital Rights in Spanish) released a new report titled “Who defends your data?” analyzing information from the largest telecommunication service providers in Chile: Claro, Entel, GTD Manquehue, Movistar, VTR, and WOM. The report shows a sustained advance of internet provider companies in terms of data processing practices of their customers. “Who defends your data?” is part of a series of similar studies carried out in Latin America and Spain, based on "Who Has Your Back?", a periodica; report published by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) in the United States. Its methodology was adapted by Derechos Digitales in the Chilean context.

Brazil holds the second round of Presidential elections in the midst of aggressive digital campaigns

After the first round of elections on October 2nd, Brazilians will elect their President and some governors on October 30th. This second round of Presidential elections will determine whether the candidates Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Jair Bolsonaro will win.

The election campaigns have been accused of running fake news and disinformation campaigns. Check out Sleeping Giants Brazil, a consumer movement against funding hate speech and fake news in Brazil.

...

Author: Islam al Khatib

Islam al Khatib is a Palestinian feminist born and raised in Beirut. She researches feminism(s), hegemonies in the 'technocene', ecologies, and grief. She holds BAs in Political Science and Philosophy from the Lebanese University (LU). She is currently pursuing a masters in Gender, Media and Culture at Goldsmiths, University of London.

MENA Regional Brief

Current Opportunities for Digital Rights Defenders in MENA

Digital Capacity Building Program for Content Creators with Ananke:

Ananke is a new media and development platform that has its own lab initiative and are currently hosting workshops for women and girls on capacity building on inclusive content creating processes. Deadline: 25th of November. Apply here.Registration for Bread&Net2022 is now open!

Bread&Net2022 is a great opportunity for digital rights defenders and those interested in learning more to network and exchange knowledges. Registration is free. Deadline: 1st of November. The program is finally out! Make sure to register here.

Emerging Topics on Digital Justice in MENA

Controversial Meta’s Human Rights Assessments: what can digital rights defenders do?

After years of demands and campaigning, Meta finally released its first human rights report in July 2022. The company conducted several assessments in various contexts, including the US presidential elections and the elections in Myanmar. However, the report published only a portion of the Human Rights Impact Assessment (HRIA) on India, which the company was compelled to conduct as a result of numerous civil society campaigns.

Following criticism from civil society groups, the company initially commissioned the India HRIA in 2019. It was intended to independently evaluate Meta's role in spreading hate speech and inciting violence on its services in India. Meta’s report did not show the ways in which the company was complicit in this violence and thus, several human rights organizations questioned Meta’s commitment to actually combating the spread of harmful content in India. Instead, Meta deflected responsibility by emphasizing the roles of third parties and end users.

Meta has been attempting to comply with global civil society and digital justice campaigns by hiring third-party consultancies and law firms to investigate "possible violations" in different occasions. For example, Meta hired BSR, a third-party assessor, to "conduct a thorough examination to determine whether Facebook's content moderation in Arabic and Hebrew, including its use of automation, has been applied without bias," with the report due "in the first quarter of 2022."

Another case is the Meta’s report on Palestine, which was finally released this past September after a long delay .Here, it is important to note that the India HRIA was conducted by Foley Hoag, an independent law firm that interviewed over 40 civil society stakeholders, activists, and journalists to complete the report, (whereas BSR is a sustainable business network and consultancy).

Several organizations, including 7amleh, welcomed the report on Palestine while highlighting the need to immediately publicly release the full HRIA report on India. Following this, civil society organizations in Arabic-speaking countries demanded Meta to immediately release India’s HRIA in a joint letter, in an attempt to also understand the India HRIA as a foretelling sign of what is to be expected from Meta.

Meta's Appropriation of Human Rights Rhetoric

To better understand the context of these reports and to identify ways that digital rights defenders in the MENA can support these efforts, I interviewed Dia Kayyali, the Associate Director for Advocacy at Mnemonic, an NGO dedicated to helping human rights defenders effectively use digital documentation of human rights violations and international crimes to support advocacy, justice, and accountability.

Following the joint letter and demands to release the India HRIA, Meta responded that they are in no way “deflecting responsibilities” and that they are the “first tech company to issue such reports”. Meta made sure to use Human Rights legal advocacy language and terminology to defend their decision on not releasing the assessment, repeating that they are “in compliance with the UN working groups on Businesses and Human Rights values”.

Kayyali commented saying that Meta is interested in managing "divide and conquer tactics, where they hold different levels of release for different HRIAs." Meaning, "when there's media attention, they'll do a more thorough HRIA," and "that's how they got away with not releasing the India assessment" due to a lack of media. According to Kayyali, Meta is attempting to push civil society organizations into “letting them off the hook”. However, they also stated that organizations and campaigners will not allow Meta “to do one thing for a community and ignore another”.

Another layer in Meta’s rhetoric that needs to be addressed is their language, and how that is now translated in them replying to civil society organizations using their own terminologies of rights. On this, Kayyali stated that digital rights defenders need to be “crystal clear about what we mean when we say “human rights impact” and ''audit” as to not let Meta and other companies get away with non-compliance by being vague.

Meta and other companies, according to Kayyali, have been doing this co-optation tactic in advocacy spaces, where “they will comply with the demand but not with the spirit. For example, they will conduct an independent review but have most of it redacted”. Civil society organizations have asked Meta to release the assessment, and now they are asking the law firm to state whether Meta has a final say on whether they release the report or not. Kayyali says: “It’s important to be clear, especially with the required audit under the digital services industry, because there are different standards for different assessments”.

Third-party consultants industry in development

When responding to a question on the fact that Meta is relying on third-party organizations and what that means in terms of transparency and accountability, they said that “it is not irrelevant that a law firm did the India HRIA and a human rights consultancy did it for Palestine. It’s important to ask who is doing the consultancies”, a note that is important to highlight is an increasing reliance on third-party consultancies in the digital rights sector, which have now almost formed their own industry.

When asked about tactics and the ways in which digital rights defenders in the MENA in particular can engage with these issues and questions, Kayyali highlighted the need to be clear about demands and to understand the language of the company you are advocating against.

They also emphasized that there can be room for different ways of doing digital justice work around this: “there’s always a need and room for diversity of tactics. There’s room for people who do not want to engage with companies and that’s an important part of our space of human rights and tech. There’s also a need for people who are building alternatives, that’s another layer of the ecosystem. While I am demanding rights from Meta, there are people who are focusing on building decentralized platforms. What we all do is harm reduction. It’s important that we do not message in ways that delegitimize each other’s work”.

Another recommendation according to Kayyali is “to engage more people in digital rights conferences, opening up spaces for smaller and different organizations. There are some big known organizations that are sort of the faces of human rights and tech work in the region for the rest of the world which is unfortunate. It is exciting to engage completely different people who are making the same arguments, some from a slightly different perspective which help us better our understanding of what is happening”.

It is also important, from Kayyali’s perspective, to understand the work on India’s HRIA as a way of networking and bridging the gap of communication between the region and Southeast Asia. On this note, Kayyali says “we need to understand that we have more in common with Southeast Asia in terms of bias and resourcing. For example, human rights defenders from Egypt and Gulf countries have a lot to share with human rights defenders in India”. A request from Kayyali would be to refocus attention on calls to release the India HRIA and to connect with networks in and outside of India. Dia Kayyali will have a session in Bread&Net2022, which you can register for here.

Community News

#FreeAlaa

Alaa Abdel Fattah, an Egyptian-British pioneer in open source technology and an Amnesty Prisoner of Conscience, has been imprisoned in Egypt since November 2019 amid inhumane conditions. Alaa has been on hunger strike for over 200 days, protesting against his unjust detention. His family are greatly concerned about his deteriorating health.

Sanaa Seif, the sister of British-Egyptian detainee Alaa Abdel Fattah, began a sit-in in front of the UK's Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

FreeAlaa.net has an action you can take. Sign here: https://freealaa.net/take-actio.

Iran’s protests

Iran’s protests following the murder of Mahsa Amini (Jina Amini) continue. Given the context of censorship, several companies and organizations are developing or consolidating VPN tools and resources to circumvent censorship. In the face of this, authorities are in the process of criminalizing VPNs. For more information on Internet Freedom tools, resources and actions to dupport Iran's Feminist Uprising, read this blogpost by Team CommUNITY.

Egypt increases checkpoints ahead of #COP27

Egypt is hosting the 27th Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC (COP 27), the United Nations climate summit. It will be attended by world leaders and leading climate activists. In fears of potential protests, the Egyptian government is holding arbitrary checkpoints and conducting unlawful phone checks looking for any content on their social media and messaging apps that they could deem critical of the regime.

Regional News and Updates in MENA

Image’s source: Stikywork, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

An investigation into TikTok’s “middlemen”:

BBC News investigated a new TikTok trend in which hundreds of families in Syrian refugee camps begged for gifts on TikTok live streams, the children would go hours at a time for any livestream.

For five months, the BBC tracked 30 TikTok accounts broadcasting live from Syrian refugee camps in which they learned that viewers were frequently donating digital gifts worth up to $1,000 per hour to each account. Families were only receiving a fraction of the amount being donated.

After Tik Tok refused to disclose any information or finances, the BBC team conducted an experiment to determine how much profit TikTok is making. The team then discovered that TikTok receives 69% of the money, while the middlemen, or those with phones and internet access who allow the families to live stream, receive 35%.

Legislators all over the world have criticized TikTok for allowing children to become content. In a report on child influencers released in May by the UK Parliamentary Committee, the committee stated that legislation is "urgently needed" and that not all parents are acting in the best interests of their children. TikTok was also scrutinized for its data privacy practices. From May 2018 to July 2020, allegedly processing data of children under the age of 13 without parental consent. Access Now's Marwa Fatafta denounced in an interview with BBC TikTok for "creating and enabling an ecosystem that runs on the exploitation of people's suffering in violation of its own policies and of the human rights in violation of its own policies and of the human rights" of displaced Syrian families."